In the previous article, "What's wrong with Ukrainian Figure Skating Federation?" we talked about sports governance models – Soviet, North-American, and European – and briefly mentioned the fact that they work well if they are aligned with a country's governance system. But we didn't expand much on what it actually means.

Sometimes it literally means matching the political and social structures of the country. For example, in Belgium, almost all sports have two federations – French- and Dutch-speaking ones. Or in Spain, already existing club system was substituted with a centrally governed structure with National Sports Delegation during the 40 years of Franco's dictatorship, and then switched back. But mostly it means reflecting principles the society is built upon, and the club system is a perfect case to explain this.

The nature of the club system

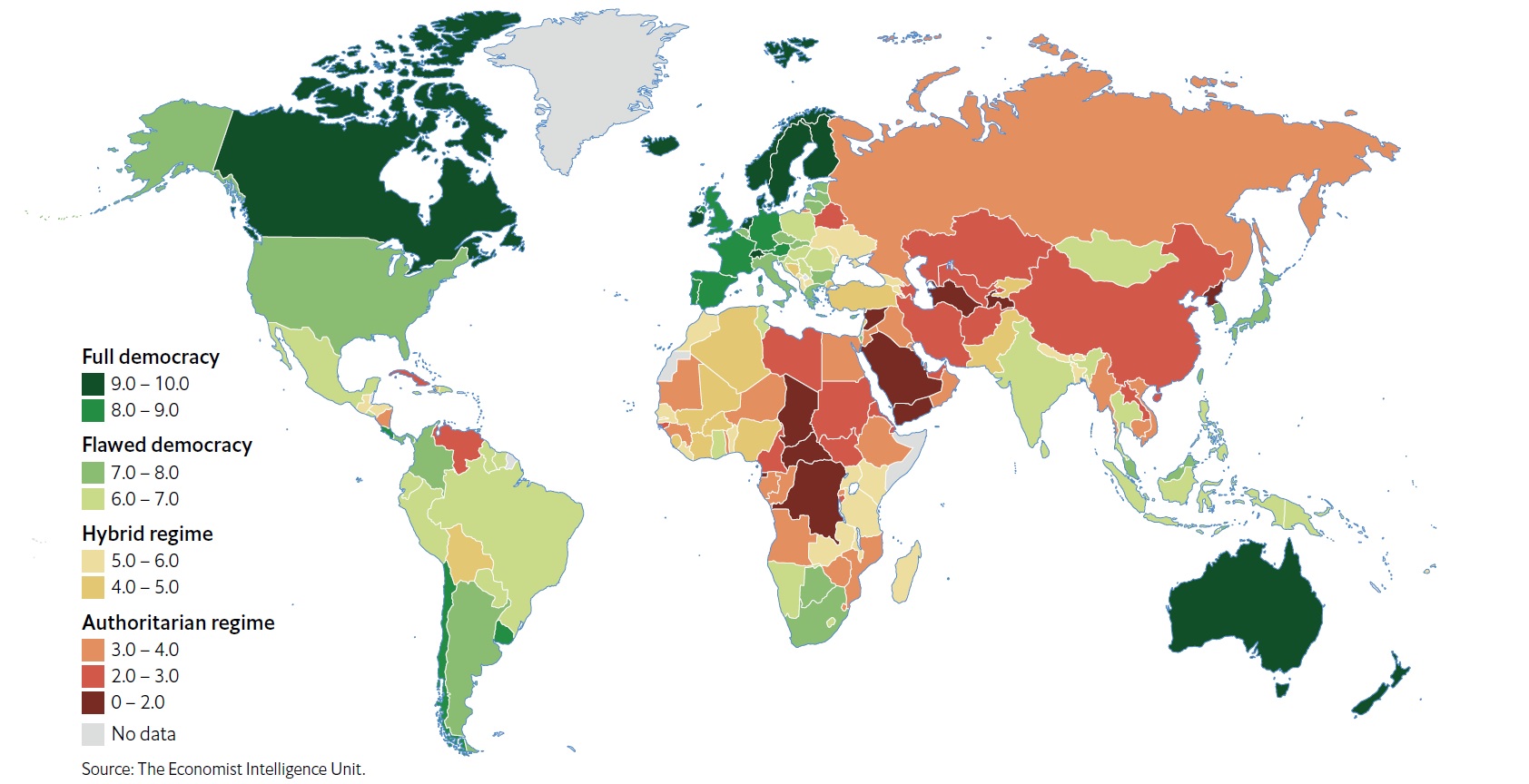

Club system is at the heart of all sports governance models in all European countries, in the USA, Canada, Australia, Japan, and in some other countries at the top of the democracy index list:

There is a good reason for that. Democracy is about people having the freedom to rule as they want, as opposed to a small number of people ruling over everyone else.

People naturally love sports and want to play, learn, participate, watch, and be engaged in sports. It's in their best interest to unite their forces with others and form groups. It's just easier and cheaper to achieve basic sports needs as a group rather than an individual – "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts". When two or more people, who love the same sport, dwell in the same space (geographical or virtual) and share basic democratic principles, meet and decide to join their efforts – it's already a pretty good description of the club.

The sports club is a self-organized group of sports enthusiasts, who are interested in further development and practicing a particular sport. Notice the word "enthusiasts" – it's important to understand that passion for sports and enthusiasm underpins the club creation.

When more clubs start communicating and doing anything that requires some degree of coordination – like organizing competitions or sharing infrastructure – the most natural solution for them is to form association or federation. For already established sports disciplines national federation must represent international body for the given sport, and for the new sports disciplines, federations might be willing to create a new one to coordinate on the international level.

The whole system is organized along a pyramid structure, with clubs providing a foundation for it. Clubs enable different social and population groups to participate in sports (known as "sport for all" approach) and provide a basis for the elite sport.

Three main principles hold true:

- clubs are self-organized and participation is voluntary

- a sports club is the main building block of the whole system

- the structure is built from the bottom up

and it happens naturally.

In other words, the club system is what happens when the government doesn't tell people what to do in sports.

You may wonder how these self-emerged structures made it into the national sports governance system? The answer is simple – in democratic societies policy and the law-making process is mostly about capturing what people believe in and codifying it into the law. This may sound unusual to the Ukrainian people, but that's how the law-making is supposed to work.

The bottom line is, the club system is the most natural form of sports organizations in democratic societies.

Sports clubs and legal status

In all countries, a sports club is simply a non-profit organization voluntarily created by people who have passion and experience in the given type of sports. There are no special requirements for an organization to be a sports club, but here are some key features common for sports clubs:

- voluntary membership – members decide individually on their entry or exit (unless federations establish athlete transferring regulations for elite level clubs).

- orientation towards members' interests – members are retained via joint interests, not by monetary means.

- democratic decision-making – to serve members' interests, the club has to have a process of capturing its members' opinions and allow them to influence the club's goals.

- autonomy – clubs don't depend on other institutions or organizations to achieve their goals and finance themselves mostly via internal sources.

Clubs are usually non-profit organizations – which means that a surplus of revenue is used to further develop the club rather than be distributed between club members. Sometimes it's legally required, sometimes not, but in most countries, non-profit status is essential to get additional support from the government, so it's the most common legal form of the sports club.

Creating a legal person, conducting accounting and other bureaucratic things might be a burden for small and simple clubs, so in some countries, sports clubs exist without a legal person at all. A notable example is the UK's unincorporated associations, which are ruled only by its own constitution and are very cheap and easy to form. The downside, of course, is the inability to involve in contracts or hire stuff, which is usually solved through trustees and members of the club that have their own legal person and act on behalf of the club.

Sports clubs and the government

This leads us back to the topic of the sports governance system. If a club is a self-organized autonomous voluntary non-profit organization, what's the role of the government here?

Essentially, there is not much need for government involvement at all. If people have enough freedom to self-organize, have all tools needed to create clubs and associations, and coordinate their efforts – there is no need for yet another layer of bureaucracy and governance.

In most countries, though, governments are interested in sports development as well and invest in it through direct or indirect financing – subsidies, grants, tax exemptions, and so on. In order to channel those funds in a transparent and fair way, governments maintain registers and statistics about its sports basic units, sports clubs, and want some level of accountability for those funds through umbrella sports organizations.

So, theoretically, clubs can exist without any involvement or interaction with the government, but in practice, they're incentivized to at least register in the national database of sports clubs. The major incentive, of course, is financial support and funding from the government, where clubs can be seen as providers of the service the government wants (whether it's an increase of public wellbeing through sports or country's prestige in the international arena). This often comes in the form of access to the municipal infrastructure (which is usually crucial for sports like figure skating) and grants.

It's not limited to funding though. Sometimes non-monetary incentives are also used by government bodies to get desirable outcomes from sports clubs. As an example, Sport England (a government body that oversees sports in the UK) has a licensing scheme for clubs named Clubmark (after Kitemark, a well-known name in England associated with quality). Clubs accredited for this license not only get preferential access to some facilities and additional funding but also are recognized as safe and adhering to the best coaching practices, so people would prefer them over non-accredited clubs. Being accredited a Clubmark status is already an achievement the club would brag about on every occasion:

The point is, clubs are the basic form of sports organizations, and governments simply acknowledge it and base their support system around it. Most countries do have some sort of bodies formally known as "ministries of sports" (usually as a Ministry of Culture and/or Youth and Sports, but naming varies – like "Sport England" mentioned above), but they shouldn't be confused with a Soviet-type Ministry of Sports. A sports ministry in a club-based system usually maintains a high degree of independence from the government while working closely with other bodies, and mostly deals with sports funding.

Sports clubs' size

"Club" is quite a general word and doesn't tell anything about the scale of the organization. As with the word "company", which equally applies to a 2-person startup in a garage and to a trillion dollars worth corporation, clubs might be small groups of just a few people or multi-thousand world-known organizations that have their stocks on the stock exchange.

A group at a local ice rink with just one coach and a couple of athletes is a club. So is Real Madrid mutually owned by about 50000 people who elect a president to run the club.

Size distribution and forms for clubs vary from country to country, so using averages don't say much, but in the academic literature the most common classification seems to be the following:

- small clubs – less than 100 members

- middle-sized clubs – 100-500 members

- large clubs – 500+ members

The majority of clubs seem to belong to the small clubs' category.

Sports clubs and finances

Speaking about finances, sports clubs need financial health to operate. Since sports clubs are predominantly non-profits, in which people with common passion and a goal organize sports activities, their main financial challenge is to balance revenues and expenses, not to make profits.

Clubs mostly rely on two types of revenues – internal and external. Internal revenues come from the club members in various forms and external – from the community, state, and other external stakeholders. The most important internal revenue sources are the membership and admission fees, which are usually moderate, as clubs strive to be affordable for different population groups. Many European figure skating clubs, for example, have membership fees at around 30-60 EUR per year or ~3-5 EUR per month (100-160 UAH).

Other internal revenue sources include club activities like competitions organization, commercial activity such as operating ice rink cafe, or merchandise selling (non-profits are allowed to do so as long as the income goes into the club budget) and fundraizing events.

For the external revenue sources, government subsidies, grants from municipalities, and sponsorship deals are the most important.

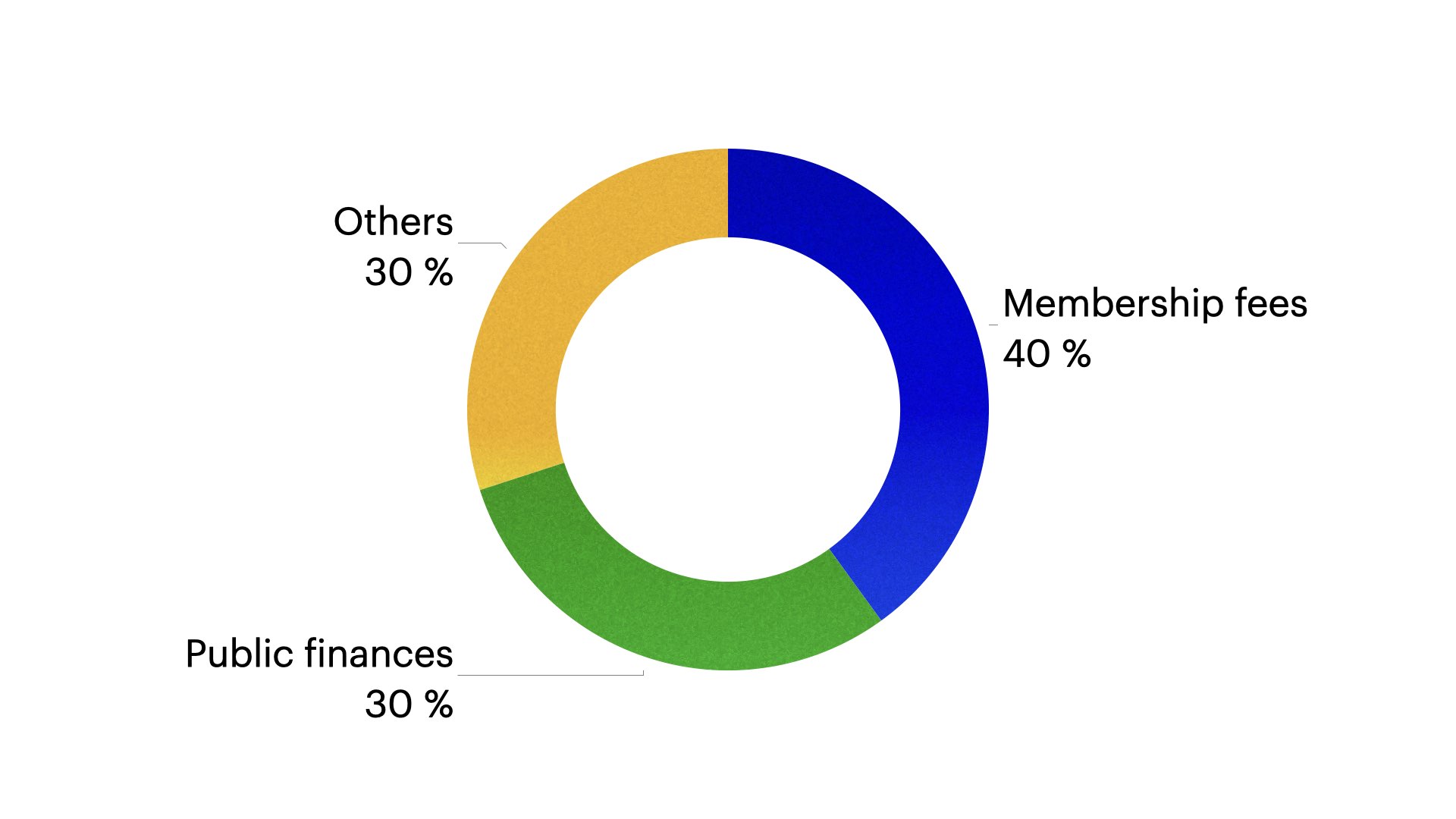

Again, it's hard to provide averages here, as the situation differs drastically from country to country, from sport to sport, and varies between different types of clubs. But in a very rough generalization, it seems like the typical revenue source distribution looks similar to this:

- membership fees – 40%

- government subsidies – 30%

- sponsorship, commercial activity, fundraising – 30%

Now, managing the financial health of a club is not always easy. It requires some degree of finance management expertise, understanding of portfolio diversifications, risk/benefit ratios of different revenue sources, and other concepts from financial management common in business. For example, membership fees are seen as low-risk and stable because they come in small units (per each member) and predictable, but government grants usually come as an all-or-nothing packages and depend on the political situations and other factors. One cautionary tale is Czech municipalities sports budget dependence on the national sports lottery SAZKA, which collapsed in 2011 – clubs that depended heavily on grants have had a hard time in the subsequent years.

It's important to understand that the club budget is exactly what it says – it's the money club has to realize its own goals. Usually, it means paying general costs and regular sports operations – administrative fees, renting the facility, advertising, taxes, traveling to competitions, and so on. Sometimes it includes salaries for the club's board of directors, but more often than not it's also a voluntary position. Coaching services are usually paid separately – through the club's coaching packages or on an individual basis – it's up to the club to choose the approach that works best.

Sports clubs and public financing

As was mentioned earlier, one of the important revenue sources for sports clubs is public finances in the form of grants from municipalities and access to sports facilities. The proportion of this source to the total club budged varies from country to country and seems to be within the 10-40% range.

In theory, clubs' financial receipts should be enough to fairly redistribute financial and facility support to a new club. In practice, however, this process is rarely smooth and usually involves maintaining good relationships with all involved parties. Corruption cases are not unheard of, but still, the whole system is designed for transparency and fairness in mind.

Public financing usually comes in a few forms:

- Basic funding – basic funding is the financial subsidies awarded to clubs on a per-member basis. Some countries calculate the club share from the total number of members, or the number of members in a particular group age (i.e. <25 years) or include other factors, like the number of licensed coaches. Sometimes this is organized in forms of vouchers, sometimes it's based on a self-reported number of members from clubs (with mechanisms set up in place to verify the validity of these numbers).

- Sports facilities – state and municipal governments often build, maintain, and provide sports facilities. Ice rinks, in particular, are notoriously expensive to build and maintain, so it's virtually impossible for clubs to build their own rinks. One of the main jobs for municipalities is to maintain and provide access to these sport facilities, so they manage the allocation of access to the clubs and may give subsidies for clubs that want to take over the maintenance instead. Additionally, local governments may fund the building of new facilities in form of investments.

- Target groups and health programs – additional funding often granted for clubs that offer special programs, wich the government sees as beneficial to wider population groups. This may include programs for elderly people, people with disabilities (adaptive sports), migrants, and underrepresented groups. Those funds increase social participation in sports and help promote "sports for all".

- Elite sport – clubs also eligible for subsidies related to the elite sport matters – hosting competitions, traveling, organizing training camps, and so on. The state usually supports elite sport through grants distributed through federations to the clubs, as those are fundamental building units for creating, fostering, and developing talents.

To receive subsidies clubs must first comply with basic requirements (be registered in the sports system, be a member of a national federation and so on) and go through the application procedure explaining the funding goal and how money is going to be spent.

Sports clubs and voluntary work

There is another important aspect of the economic sustainability of sports clubs – voluntary work. Voluntary means that performing this work is not mandatory and is usually unpaid. But, generally speaking, clubs enjoy the luxury of having people united around a common goal and driven by the enthusiasm and passion towards their sport. Many clubs offer its members something more important than just sports services – it's the belonging to the community, identification, and association with a likeminded people or the club where the famous athlete was training, moral support, and life-lasting friendships. For some sports club may become "a second home", which says a bit about a level of bonds that may exist in a sports club.

Thus, it seems natural that members are willing to help their club by volunteering their time or skills, free of charge, or for symbolic compensation. The range and type of voluntary labor is huge – from the positions on boards of directors to driving Zamboni. The most common activities are organizing and running competitions, maintaining sports facilities or equipment, being a treasurer, director, coach, or an instructor at the club and performing day-to-day club tasks. People might be willing to provide their transport for traveling to competitions, and proudly paint their car with the club's logo.

Club's branded vehicle of an ice skating club in Northern Italy. Ivan Danyliuk

Club's branded vehicle of an ice skating club in Northern Italy. Ivan Danyliuk

The form, number of hours, types and popularity of voluntary work in sports clubs widely differs from country to country – probably more than anything else. In the USA, for example, voluntary participation is usually expected from all members, which is communicated on membership applications. Members usually should spend 8-10 hours a year volunteering at any position that they want or pay upfront a fee (usually equal to membership fee). In Scandinavian countries, though, parental volunteering seems to be the most common form of running a club or sports events, with parents voluntarily performing most of the work. Typically, volunteers may spend 2-15 hours per week for their sports clubs.

It's hard to assess the economic importance of voluntary work in a sports club, but one study in France estimated that 1 million volunteers provide 300 million work hours. Take a moment to appreciate the sheer number of the voluntary work done in a sports club, and realize that without voluntary participation all those hours would have been paid from budgets according to the market wages. No surprise that the same study calculated the economic value of voluntary sport participation to be around 15 times higher than the total expenditure for sports in France.

The key point here to understand is that sports clubs can capitalize on the intrinsic voluntary nature of the clubs, which creates other motivations for work than financial. People often chose to volunteer in sports clubs to satisfy their family and community needs, help and meet people, make friends, plus increase their reputation and power within a club too.

Developed sports organizations harness the power of voluntary work as much as they can. United States Figure Skating Federation, for example, states it boldly that volunteers are at the heart of it, and encourage people to volunteer at local and international events and at their local clubs. Skate Canada, a Canadian figure skating federation, goes further and organizes an annual Volunteers Award ceremony, where volunteers are honored with prizes and recognition. This year this ceremony was held online due to COVID pandemic, but here is a video from 2013 to get the sense of how important the volunteering is to Skate Canada:

How to create a club?

Let's take a look at the step-by-step process of founding a sports club in the club system.

Unsurprisingly, it starts with googling "How to create a club?" and clicking on the first couple of results, which, thanks to the smart Google algorithms, usually leads people to websites dedicated to sports clubs in their country. Since federations are unions of clubs, they usually are on the front line of helping people to kickstart a new club and provide the needed information and consulting on that matter.

One of the basic rules, common for non-profit organizations, is a minimal number of people – usually two or three persons. As the idea to form a sports club usually emerges when some informal social structure resembling a club already exists, it's never a problem. Sometimes it's a coach who moved to a new city or region, or a new infrastructure is built, and people already gather together and exercise their sports, or people in the existing club have different views on the coaching methods or the way to manage a club. The point is, clubs are never formed by the orders from above and without people already connected and united through their love for the sport.

Whenever people realize that they are ready to become a club, the next step is to register an organization. This process is similar in many countries:

- Write a bylaws (statute) document – Bylaws (constitution) document explains objectives of the club and rules on which it's going to operate, its organizational structure, and the decision-making process. Most clubs use a typical bylaws template, available on the government websites, and modify them to their needs. This document is usually posted on the club's website afterwards.

- Assign roles – Club has to have a number of roles – like President, Board of Directors, Trustees, Treasurer, and so on, which obviously might be performed by the same people, especially when the club is small.

- Register within government sports bodies – This is often mandatory for clubs that want to be eligible for government subsidies or access to the infrastructure. Clubs might be required to put special clauses in their constitution and report their annual returns to the government.

Federations also may put their requirements on the clubs to accept – like amendments of their constitutions or club sizes, but usually, it's a logical next process – join the national federation for their sport.

And that's basically it. Once the club is registered, it's up to its members to manage its activities, find and recruit new participants, handle marketing and advertisement, launch a website, pay taxes and decide salaries for coaches. In theory, only the quality of the services, the proactivity of its members, and the number of active club members define how successful clubs will be in raising funds, getting government grants, or finding facilities.

The important point here is that every person can register a club and become a part of the national sports system. How and by which means the club is going to meet its goals is up to the club.

Sports clubs and federations

As was already mentioned, in the club system federations are created from the bottom up by the most pro-active club representatives and carry on the same principles of self-organization and democratic decision-making. In its simplest form, federation can be seen as "a club of clubs" – a higher level club, which coordinates other clubs, organizes inter-club competitions, helps to agree on the sports development best practices, and so on.

Essentially, federations have three main objectives:

- bring together clubs with the aim of organizing, promoting and developing the sport

- communicate with the government sports bodies

- represent and communicate with the international organization for the particular sport

They usually deal with a larger set of stakeholders (individual members, clubs, amateur, and elite athletes, governments, sponsors, private sector, other sports bodies like Olympic committees, etc), and have a more diverse set of organizational challenges.

Proactive federations adopt and learn the best practices from successful clubs and help to share them among other clubs. They collect statistics and feedback from clubs and try to use their power and position to help mitigate common problems the club might have. They might develop sport development plans, which new clubs can learn upon. They may offer consulting services on effective club management, launch educational campaigns, or run various financial funds, from which all clubs will benefit.

The difference from the Soviet DUSSh system

Based on the information above, let's take a look at the key differences of the club system from the Soviet DUSSh system, currently used in Ukraine. On the surface, DUSSh and clubs may look similar – in both cases, they're organizations providing sports services, in both cases, there are management, coaches, and students, in both cases they have budgets, facilities, equipment, and training plans. So what differs:

| DUSSh | Club | |

| Ownership | owned by local government |

owned by a likeminded group of people |

| Starting a new one | incredibly hard | cheap and easy to create by anyone |

| Freedom | little or no freedom of choice on coaching practices | can choose from coaching programs suggested by the federation or develop their own |

| Finances | rely exclusively on local and state budget, and the main instrument DUSShs have is the hope that next year it will be better | government financing contribute to only 20-30% of the budget, and other revenue sources to large extend depend on the professionalism of the club's head members |

| Support allocation | centrally planned, local or state government decides who will get money or access to the infrastructure | "money follows the athlete" principle – reallocation happens according to how many and where actual athletes train |

As you can see, clubs provide freedom, choice, and more options for organizing sports. This effectively creates not only higher sports participation levels, but also more effective and fair funding distribution and less corruption risks. They are not limited to the activities, regulations and processes prescribed by the government, as DUSSh are.

What is even more important, is that the club system effectively creates competition on all levels – for better coaching, for better communication, for better results, for better utilizing of resources and finances and pretty much everything else. Clubs that only rely on state budgets and do not adapt will not survive the competition. Abusive coaching practices will lead to the majority of members switching to another club (or creating a new one). Ineffective or corrupted management won't survive competition either.

A club is not a silver bullet

It's important to understand, that a club doesn't automatically mean a great experience or financial sustainability. Managing a club is a challenging work, and having administrative and business-related experience often helps to run the club efficiently. There is no single best way to run a club, rather it's the club's job to react to the internal and external challenges and adopt their ambitions and activities accordingly.

The atmosphere in the club also is something that differs wildly from club to club. In the end, clubs are social structures and personalities of the core club members matter – especially in small clubs. It might be the loveliest place in the world for its members, where they find their best friends and second family, or it could be the abusive depressive environment with toxic culture and a high churn of staff.

Myths about the club system

There are plenty of myths circulating regarding the club system in Ukraine. As it always happens, myths surround topics that are poorly understood, so, hopefully, this article clarifies things a bit. Anyway, I want to address some of the most common myths:

Myth No. 1: Clubs are expensive, it's not for Ukrainian economy

This myth is often based on the personal experiece of coaches and athletes visiting sports clubs abroad. As soon as they hear the prices and compare them with Ukrainian wages, they're quick to jump to a conclusion that club system is inherently expensive. They rarely take an opportunity to learn about the club budget formation, sponsoring practices and volunteering, public funding, let alone adjust the prices.

The truth, of course, is different. To start with, state-prescribed wages for DUSSHs coaches created nothing more but the shadow sports economy, where majority of money is paid to coaches anyway in cash. It makes it almost impossible to research and analyze, but this shadow economy is undoubtely much bigger than the official Ukrainian state's sports expenditure. Based on my anecdotal evidence I collected over the years, my rough estimation for it in figure skating is that the number is at least 10-20 bigger. I might be off for an order of magnitude, though. A club system simply moves this financial flows from the shadow into the light, where it'll create proper incentives and accountability.

Next, club system is not prescribing any particular prices at all. Remember, it's about the freedom to choose whatever forms of organization, operation or pricing you want. That's a nice property of market economy that prices self-regulate and eventually settle down on the optimal intersection between what people can pay and at what price the services can be offered. Club system will find it's optimal balance in Ukrainian economy, don't worry for that. Economic forces work no matter how well they are understood.

Myth No. 2: Clubs are for amateurs, DUSSh is for professionals

The nice thing about clubs is that, again, they have freedom to choose what's their speciality is. Brian Orser, the world's most renowed coach these days, trains in the Toronto Cricket and Skating Club, for example. It's a large club, with many sports represented in it, but it's still a club.

It's true that elite sports often require a higher financial support and is of a higher interest for the government. Governments often sponsor elite sports through public funding discussed above. In Estonia, for example, there is a concept of "sport schools" (probably a remnants from the old Soviet system), which have more financing from the government, but in practice it's just a special license a skating club should get. In any case, clubs are the basic unit that provides coaching and other sport services. Clubs can be either amateur or professional, for children, youth, or adults, single-sport or multi-sport and so on.

Amateur vs professional in terms of club system is simply a false dichotomy.

Myth No. 3: Clubs aren't free, so poor families are left behind

There is never a free service. In Soviet system, "free" means that state pays for it. Clubs aren't free, but it doesn't mean they can't provide services for low-income families. Public funding from state and local government often targets these social layers, so clubs are incentivized to provide programs and classes for various groups.

Even more, as clubs are often organized by socially pro-active people, it's not unusual for clubs to actually pioneer different programs to support low-income or underrepresented social groups. Again, most clubs aren't businesses, and their goal is not to maximize the profit by all means.

Club system in Ukraine

In the previous article, we mentioned that Ukraine will most likely transition to the European club system in the near future. But this transition has already begun many years ago. Remember at the beginning of the article we mentioned that it's the most natural form of sports organization for people? Well, Ukraine already has a club system emerging unofficially in parallel to the official sports governance model. It exists in shadows, mostly invisible to the government and/or federations.

As an example, many running clubs do exist in Ukraine, with people being united and organized around their passion for running. They bring together thousands of people in many cities, they organize marathons and practice camps, practices, training camps, travels to international marathons, provide support, have their own budget, promote themselves on social media, and... do not exist for the Ukrainian sports system. They never bother registering as a club for two reasons:

- Ukrainian sports system doesn't give them any reason or incentive to do so, while bureaucracy levels are quite high;

- nobody around them is doing that, there is no "culture" of clubs yet.

Thousands and thousands of Ukrainian people already participate in some sort of sports clubs, without even knowing that in other countries they would be called a club, would be registered and recognized by the government, and eligible for its funding and help.

Some sports federations, especially the ones that depend less on the infrastructure and funding, already understand and recognize the need to switch to a club-based system. Ukrainian Athletic Federation, for example, communicates the need to switch and recently conducted a webinar dedicated to the club system. Another not widely known example is a Ukrainian Karate Federation, which made a transition from the old Soviet-style corrupted federation towards the modern club-based federation. Karate only recently has become an Olympic discipline, and was prohibited in USSR – the rumor says Soviets thought it fostered rebellion spirit – which might explain the success of pioneering the club system in Ukraine.

In figure skating, a club system also slowly starts to emerge in cities that historically were outside of the UFSF control. We will cover these stories in the next article(s), but it's striking how it already creates fair competition and driving quality of services provided by the clubs. The governance and processes inside these clubs are also remarkably similar to European clubs, without people even being aware of it. Which supports the point made at the beginning of the article – club system is what happens when government doesn't tell people how to do sports.

One thing is clear – transition to the club system is inevitable, and Ukrainian government should harness and lead it. Ukrainian sports community should start a nationwide discourse and push for the changes in the laws as well. It's not enough to rename DUSShs as "clubs". People should embrace the new paradigm that the club system brings – a competition for quality of service on all levels. "Money follows the athlete" will create a fair and more effective way to develop sports in Ukraine, and increase the overall quality, satisfaction, and sports achievements of Ukraine in the international arena.

Hopefully, this article gave a bit of the high-level understanding of what a club system is. We'll be covering the club system development in Ukrainian figure skating in the next articles and discuss perspectives of it in Ukrainian sports. Stay tuned and let us know what you think.